Show Boat

| Show Boat | |

|---|---|

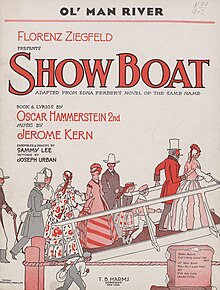

Original 1927 sheet music for Ol' Man River, from Show Boat | |

| Music | Jerome Kern |

| Lyrics | Oscar Hammerstein II |

| Book | Oscar Hammerstein II |

| Basis | Show Boat by Edna Ferber |

| Premiere | December 27, 1927: Ziegfeld Theatre New York City |

| Productions | 1927 Broadway 1928 West End 1932 Broadway revival 1946 Broadway revival 1966 Lincoln Center revival 1971 West End revival 1983 Broadway revival 1994 Broadway revival 1998 West End revival 2016 West End revival |

| Awards | Tony Award for Best Revival Olivier Award for Best Revival |

Show Boat is a musical with music by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. It is based on Edna Ferber's best-selling 1926 novel of the same name. The musical follows the lives of the performers, stagehands and dock workers on the Cotton Blossom, a Mississippi River show boat, over 40 years from 1887 to 1927. Its themes include racial prejudice and tragic, enduring love. The musical contributed such classic songs as "Ol' Man River", "Make Believe", and "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man".

The musical was first produced in 1927 by Florenz Ziegfeld. The premiere of Show Boat on Broadway was an important event in the history of American musical theatre. It "was a radical departure in musical storytelling, marrying spectacle with seriousness", compared with the trivial and unrealistic operettas, light musical comedies and "Follies"-type musical revues that defined Broadway in the 1890s and early 20th century.[1] According to The Complete Book of Light Opera:

Here we come to a completely new genre – the musical play as distinguished from musical comedy. Now … the play was the thing, and everything else was subservient to that play. Now … came complete integration of song, humor and production numbers into a single and inextricable artistic entity.[2]

The quality of Show Boat was recognized immediately by critics, and it is frequently revived. Awards did not exist for Broadway shows in 1927, when the show premiered, or in 1932 when its first revival was staged. Late 20th-century revivals of Show Boat have won both the Tony Award for Best Revival of a Musical (1995) and the Laurence Olivier Award for Best Musical Revival (1991).[3]

Background

[edit]Ferber and her novel Show Boat

[edit]

In April 1926, Edna Ferber's fifth novel, Show Boat, began publication in a serialized version in the magazine Woman's Home Companion (WHC).[4] The complete book was released in August 1926 by Doubleday, Page and Company before the magazine series finished the following September.[5] The work was unusual content for a women's magazine of the period, with its inclusion of taboo subjects like infidelity, desertion, single motherhood, prostitution, gambling, and miscegenation.[6] It was well received by both the public and the critics from the beginning, and the author received offers for film adaptations after the first two installments of the novel were published in WHC.[7] It became a best-selling novel.[8]

It centers on Magnolia, the daughter of the owners of a showboat, Cotton Blossom, Captain Andy Hawks and his wife, Parthy. Musically gifted as a child, she learns from the ship's performers and from the Cotton Blossom's black cook Queenie and her husband, the dock worker Jo.[a] Despite her mother's opposition, Magnolia becomes an actress and singer on the boat's stage. She falls in love with her co-star, gambler Gaylord Ravenal; they marry and have a child. Ravenal's gambling addiction and huge debts, philandering with prostitutes, and ill health lead him to abandon his family. Magnolia manages to move on and thrive because of her prodigious singing talent; she is described as a white woman gifted with the singing voice of a black vocalist.[9][10] Musicologist Todd Decker stated,

"Magnolia's embrace of show business as a means to survive as a single mother is directly linked to Ferber's use of black music to characterize her heroine. Magnolia's black voice thus proves a defining aspect of Ferber's main character and a central pillar of the novel's structure and larger themes. Magnolia's story and the plot of Show Boat alike trace the course of American life across the divide separating the nineteenth century from the twentieth, an epochal shift felt with particular power in the 1920s when the effects of World War I and a series of overlapping transformations in daily life were altering the fabric of the nation."[11]

Ferber's novel was inspired by a conversation she had with the producer Winthrop Ames in 1924.[12] Ames, to whom Ferber dedicated her novel,[13] was producing Ferber's play Minick, which was preparing for its Broadway debut; its tryout performances were not going well. Following a difficult day, Ames joked that they should all join a showboat if the play flopped. Ferber had never heard of a showboat, and her curiosity began her fascination with 19th century showboats on the Mississippi River.[12] She began months of research [14][12] and became an expert on the types of 19th-century paddle steamer ships active on the Mississippi.[15]

She boarded the James Adams Floating Palace Theatre in April 1925,[12] leaving North Carolina,[14] and spent five days on the ship while it traversed the Pamlico River.[16] Ferber described the voyage as resulting in a "treasure trove of show-boat material, human, touching, true".[17] Onboard, she attended rehearsals and took on jobs from selling and taking tickets to performing small roles. She also spoke with audience members.[15] The ship's captain, Charles Hunter, hosted the trip.[14] Much of the world of the novel was based on stories he told to Ferber. One, involving a family of showboat performers with mixed-race children, were the basis for the novel's subplot of the characters Julie and Steve.[18] Julie, a mixed-race woman passing as white, and her white husband Steve broke miscegenation laws of the era by marrying.[19]

Magnolia was a typical heroine of a Ferber novel, who tended to base her female leads on her herself.[15] Magnolia is a confident woman who, with pluck and determination, succeeds in business without the help of a man. While the character marries, it is a failed marriage, and she rises above the weaknesses of her romantic partner who leaves her through tragic circumstances.[20] Magnolia's domineering mother Parthy was based on Ferber's own mother, Julia Ferber, and Parthy and Captain Andy's marriage was modeled on her own parents' marriage.[15] Show Boat departed from Ferber's earlier writings in that it was not set in an all-white mid-western town. Her decision to set the novel on a Mississippi River boat traveling south forced her to engage with race for the first time.[21] While the central characters in Ferber's novel are predominantly white, the inclusion of secondary characters like Julie, Jo, Queenie and various unnamed black characters, provide a view of a multiracial world.[22]

The novel often presents black figures in relation to music;[23] frequent references to spirituals and other forms of music associated with African-Americans provide background for Magnolia's musical journey.[22] This choice reflected the increasing popularity in the 1920s of black singers performing spirituals on the concert stage in America.[24] Influenced by the writings of ethnomusicologist Natalie Curtis, Ferber uses the theme of African-American music as a means of criticizing the state of contemporary white American theatre.[25] At the end of the novel, Magnolia watches her daughter Kim study to become a singer and actress; only to have the life and soul of her talents driven out of her by the white music and theatre education system.[26] Ferber implies that music from black culture is more authentic, intuitive, and superior in quality than white musical culture that is restrained by education.[25] Decker wrote: "In Show Boat, Ferber used a racial argument about the sources of musical inspiration and authentic voice to support her thesis about the source of inspired versus uninspired acting in the almost entirely white realm of Broadway theater."[26]

Adapting Ferber's novel

[edit]Ferber's Show Boat was an unlikely candidate for a musical adaptation in the 1920s: Its heroine's unhappy marriage, her independence, and her grit in surviving as a single mother after being abandoned by a morally flawed husband ran counter to the typical portrayal of women in Broadway musicals as helpless victims who need rescuing.[27] And Julie's tragic subplot was far darker than Broadway musicals' typical content.[28] Rather than ending with a happy marriage to her male rescuer, Ferber's novel depicts Magnolia's marriage as the source of her problems[29] followed by her triumphant solo journey to independence and success.[30] Nevertheless, the novel's recurring music and entertainment themes made it an irresistible challenge for Kern and Hammerstein to adapt for the musical stage.[31] After the 1925 success of the musical Sunny in collaboration with Hammerstein, Kern sought a new Broadway project for the pair. By late 1926 he was determined to make Ferber's novel the subject of their next musical.[32] Hammerstein agreed, and the pair began writing material even before obtaining permission from Ferber to use her work or having a producer attached to the project.[33]

From the beginning they were determined to attract Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. as a backing producer, as they felt only he could mount a production large enough in scale to successfully portray Ferber's story.[17] They were aware that Show Boat, with its serious and dramatic nature, was an unusual choice for Ziegfeld, who was best known for revues featuring romantic comedy, such as the Ziegfeld Follies. Kern and Hammerstein worked to craft a piece that would sufficiently fill the Ziegfeld mold before approaching the producer.[34] To make Show Boat fit the Ziegfeld brand, the pair transformed the novel into a romance,[35] fundamentally changing Ferber's tale of three generations of women in a family, Parthy, Magnolia, and Kim. Kern and Hammerstein eliminated much of Parthy and Captain Andy's story, including Captain Andy's death, both to lighten the tale and refocus the story on Magnolia's relationship with Ravenal. They skipped Magnolia's childhood and relationship with her mother, and rather than concentrating on the relationship with her daughter, the musical ends with her reconciliation with Ravenal, a redemptive and more romantic arc than in the novel.[36] They also brightened Julie's story somewhat and harmonized it with broader social themes.[30]

Kern arranged an introduction to Ferber in October 1926 through their mutual friend, the critic Alexander Woollcott, during the intermission of Kern's newest musical Criss Cross.[37] Ferber was shocked by the proposal,[17] concerned that the work was not suitable for the musical genre. She felt the work's 50-year time span, and her treatment of topics like spousal desertion, alcoholism, and miscegenation did not fit the frivolous, light-hearted mold of popular musicals. She also knew that racially integrated casts of black and white actors and singers had never been attempted before on the Broadway stage.[38] Ferber was finally won over by Kern and Hammersteins' assurance that the musical would not emulate the typical "frivolous 'girlie show'" of the musical stage.[17] On November 17, 1926, she signed a contract giving the creative duo the musical-dramatic rights to her novel.[39]

Kern and Hammerstein had mostly completed Act I of Show Boat prior to presenting their idea to Ziegfeld[17] on November 25, 1926.[39] They sold their idea to him partly by building material around specific talent, such as hiring vaudeville performers into the show and providing opportunities for a chorus that featured beautiful white women.[40] They sought the star talents of African-American bass-baritone Paul Robeson. Robeson had achieved acclaim on the concert stage as a singer of spirituals and was an ideal choice to perform the spiritual-like music that reflected the music theme in Ferber's novel. To attract him, they increased the prominence of the character Joe (spelled Jo in the novel).[41] They shifted the novel's use of the Mississippi River as a metaphor for Magnolia's resilience to Joe through the hit song "Ol' Man River" to represent the resilience of the African-American laborer surviving in a racist society.[42] The torch singer Helen Morgan was another star who Kern and Hammerstein envisioned from the beginning for the role of Julie. Knowing that Morgan's popularity as nightclub singer would draw in crowds, they increased the size of the role in the musical. This also allowed Hammerstein to reshape the role into a sympathetic figure. In the novel, Julie is denounced for both her deception in passing as white and for her miscegenation. Hammerstein replaced this castigation with a sympathetic and affirming speech by Parthy in which the audience is led to see that Julie is unfairly condemned by a racist and immoral society. In this aspect, Hammerstein's libretto becomes an anti-racist and politically engaged story in a way that was not done in Ferber's novel. Julie's song "Bill" became a "musical and emotional high point" in the production.[43]

Upon hearing Act I of Show Boat, Ziegfeld was impressed with the show and agreed to produce it, writing the next day, "This is the best musical comedy I have ever been fortunate to get a hold of; I am thrilled to produce it, this show is the opportunity of my life".[44] Though Ziegfeld planned to stage the premiere at the opening on his new Broadway theatre on Sixth Avenue, the epic scope of the work required an unusually long period of development. Show Boat went through numerous revisions during tryout performances.[17] Additionally, Ziegfeld was concerned that the serious tone of the musical would not appeal to audiences and strongly disliked the songs Ol' Man River[45] and Mis'ry's Comin' Aroun.[46] He ultimately decided to open the Ziegfeld Theatre in February 1927 with Rio Rita, a musical by Kern's frequent collaborator Guy Bolton.[17] When Rio Rita proved to be a success, Show Boat's Broadway opening was delayed until Rita could be moved to another theatre.[47]

Synopsis

[edit]- Act I

In 1887, the show boat Cotton Blossom arrives at the river dock in Natchez, Mississippi. The Reconstruction era had ended a decade earlier, and white-dominated Southern legislatures have imposed racial segregation and Jim Crow rules. The boat's owner, Cap'n Andy Hawks, introduces his actors to the crowd on the levee. A fistfight breaks out between Steve Baker, the leading man of the troupe, and Pete, a rough engineer who had been making passes at Steve's wife, the leading lady Julie La Verne. Steve knocks Pete down, and Pete swears revenge, suggesting he knows a dark secret about Julie. Cap'n Andy pretends to the shocked crowd that the fight was a preview of one of the melodramas to be performed. The troupe exits with the showboat band, and the crowd follows.

A handsome riverboat gambler, Gaylord Ravenal, appears on the levee and is taken with eighteen-year-old Magnolia ("Nolie") Hawks, an aspiring performer and the daughter of Cap'n Andy and his wife Parthenia Ann ("Parthy"). Magnolia is likewise smitten with Ravenal ("Make Believe"). She seeks advice from Joe, a black dock worker aboard the boat, who has returned from buying flour for his wife Queenie, the ship's cook. He replies that he has "seen a lot like [Ravenal] on the river." As Magnolia goes inside the boat to tell her friend Julie about the handsome stranger, Joe mutters that she ought to ask the river for advice. He and the other dock workers reflect on the wisdom and indifference of "Ol' Man River", who does not seem to care what the world's troubles are, but "jes' keeps rollin' along". Magnolia finds Julie inside and announces that she is in love. Julie cautions her that this stranger could be just a "no-account river feller". Magnolia says that if she found out he was "no-account", she would stop loving him. Julie warns her that it is not that easy to stop loving someone, explaining that she will always love Steve and singing a few lines of "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man". Queenie overhears – she is surprised that Julie knows that song as she has only heard "colored folks" sing it. Magnolia remarks that Julie sings it all the time, and when Queenie asks if she can sing the entire song, Julie obliges.

During the rehearsal for that evening, Julie and Steve learn that the town sheriff is coming to arrest them. Steve takes out a large pocket knife and makes a cut on the back of her hand, sucking the blood and swallowing it. Pete returns with the sheriff, who insists the show cannot proceed because Julie is a mulatto who has been passing as white and local law prohibits mixed marriages. Julie admits that her mother was black, but Steve tells the sheriff that he also has "black blood" in him, so their marriage is legal in Mississippi. The troupe backs him up, boosted by the ship's pilot Windy McClain, a longtime friend of the sheriff. The couple have escaped the charge of miscegenation, but they still have to leave the show boat; identified as black, they can no longer perform for the segregated white audience. Cap'n Andy fires Pete, but in spite of his sympathy for Julie and Steve, he cannot violate the law for them.

Ravenal returns and asks for passage on the boat. Andy hires him as the new leading man and assigns his daughter Magnolia as the new leading lady, over her mother's objections. As Magnolia and Ravenal begin to rehearse their roles and in the process, kiss for the first time (infuriating Parthy), Joe reprises the last few lines of "Ol' Man River". Weeks later, Magnolia and Ravenal have been a hit with the crowds and have fallen in love. As the levee workers hum "Ol' Man River" in the background, he proposes to Magnolia, and she accepts. The couple joyously sings "You Are Love". They make plans to marry the next day while Parthy, who disapproves, is out of town. Parthy has discovered that Ravenal once killed a man and arrives with the sheriff to interrupt the wedding festivities. The group learns that Ravenal was acquitted of murder. Cap'n Andy calls Parthy "narrow-minded" and defends Ravenal by announcing that he also once killed a man. Parthy faints, but the ceremony proceeds.

- Act II

Six years have passed, and it is 1893. Ravenal and Magnolia have moved to Chicago, where they make a precarious living from Ravenal's gambling. At first they are rich and enjoying the good life ("Why Do I Love You?") By 1903, they have a daughter, Kim, and after years of varying income, they are broke and rent a room in a boarding house. Depressed over his inability to support his family, Ravenal abandons Magnolia and Kim, but first visits his daughter at the convent where she goes to school to say goodbye before leaving her forever ("Make Believe" (reprise)). Frank and Ellie, two former actors from the showboat, learn that Magnolia is living in the rooms they want to rent. The old friends seek a singing job for Magnolia at the Trocadero, the club where they are doing a New Year's show. Julie is working there. She has fallen into drinking after being abandoned by Steve. At a rehearsal, she tries out the new song "Bill". She appears to be thinking of Steve and sings it with great emotion. From her dressing room, she hears Magnolia singing "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man" for her audition, the song which Julie taught her years ago. Julie secretly quits her job so that Magnolia can fill it, without learning of her sacrifice.

On New Year's Eve, Andy and Parthy go to Chicago for a surprise visit to their daughter Magnolia. Andy goes to the Trocadero without his wife, and sees Magnolia overcome with emotion and nearly booed off stage. Andy rallies the crowd by starting a sing-along of the standard, "After the Ball". Magnolia becomes a great musical star.

More than 20 years pass, and it is 1927. An aged Joe on the Cotton Blossom sings a reprise of "Ol' Man River". Cap'n Andy has a chance meeting with Ravenal and arranges his reunion with Magnolia. Andy knows that Magnolia is retiring and returning to the Cotton Blossom with Kim, who has become a Broadway star. Kim gives her admirers a taste of her performing abilities by singing an updated, Charleston version of "Why Do I Love You?" Ravenal sings a reprise of "You Are Love" to the offstage Magnolia. Although he is uncertain about asking her to take him back, Magnolia, who has never stopped loving him, greets him warmly and does. As the happy couple walks up the boat's gangplank, Joe and the cast sing the last verse of "Ol' Man River".

- Plot variants in 1951 film

The 1951 MGM film changed the final scenes of the story, as well as many small details. It reconciles Ravenal and Magnolia a few years after they separate, rather than 23 years later. When Ravenal leaves Magnolia in Chicago, he does not know that she is pregnant. Through a chance meeting with Julie, he learns that Magnolia and his daughter are living on the Cotton Blossom. He goes to where the boat is docked and sees Kim playing. He talks with her; the two "make believe" that he is her "real daddy", and he weeps. Magnolia arrives and sends Kim aboard. She and Ravenal hesitate and then embrace, and she leads him onto the boat. Parthy is as happy as Captain Andy to see the reunion. Joe and the chorus sing "Ol' Man River", and the ship heads down river. Julie watches from a distance and blows them a gentle kiss as the Cotton Blossom recedes.

Musical numbers

[edit]The musical numbers in the original production were as follows:[48]

|

|

History of revisions

[edit]The original production ran four-and-a-half hours during tryouts but was trimmed to just over three by the time it got to Broadway. During previews, four songs, "Mis'ry's Comin' Aroun", "I Would Like to Play a Lover's Part", "Let's Start the New Year" and "It's Getting Hotter in the North", were cut from the show. The song "Be Happy, Too" was cut after the Washington, D.C., tryout. "Let's Start the New Year" was performed in the 1989 Paper Mill Playhouse production.[citation needed]

Two songs, "Till Good Luck Comes My Way" (sung by Ravenal) and "Hey Feller!" (sung by Queenie), were written mainly to cover scenery changes. They were discarded beginning with the 1946 revival, although "Till Good Luck" was included in the 1994 Prince revival. The comedy song, "I Might Fall Back on You," was also cut beginning in 1946. It was restored in the 1951 film version and several stage productions since the 1980s.[citation needed]

The score also includes four songs not written for Show Boat: "Bill" was originally written by Kern and P. G. Wodehouse in 1917 and was reworked by Hammerstein for Show Boat. Two other songs not by Kern and Hammerstein, "Goodbye, My Lady Love" by Joseph E. Howard and "After the Ball" by Charles K. Harris, were included by the authors for historical atmosphere and are included in revivals.[49] The New Year's Eve scene features an instrumental version of "There'll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight".

Some of the following numbers have been cut or revised in subsequent productions, as noted below (the songs "Ol' Man River", "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man", and "Bill" have been included in every stage and film production of Show Boat[citation needed]):

- Overture – The original overture, used in all stage productions up to 1946 is based chiefly on the deleted song "Mis'ry's Comin' Aroun", as Kern wanted to save this song in some form. The song was restored in the Prince 1994 revival of the show. The overture also contains fragments of "Ol' Man River", "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man", and a faster arrangement of "Why Do I Love You?" The overtures for the 1946 revival and the 1966 Lincoln Center revival consist of medleys of songs from the show. All three overtures were arranged by the show's orchestrator, Robert Russell Bennett, who orchestrated most of Kern's later shows.[citation needed]

- "Cotton Blossom" – This number is included in all the stage productions, and shorter versions were used in the 1936 and 1951 film versions.[citation needed]

- "Where's the Mate for Me?" – Included in all stage versions, partially sung in the 1936 film version, and sung complete in the 1951 film version.[citation needed]

- "Make Believe" – Included in all stage versions, and in the 1936 and 1951 film versions.[citation needed]

- "Life Upon the Wicked Stage" – Included in all stage versions and the 1951 film version but heard in the 1936 film only in the orchestral score.[citation needed]

- "Till Good Luck Comes My Way" – Cut from the 1946 revival but reinstated in the 1971 London revival. It is performed instrumentally in the 1936 film.[citation needed]

- "I Might Fall Back on You" – Usually cut from 1946 until reinstated in 1966. Included in the 1951 film.[citation needed]

- "C'mon Folks (Queenie's Ballyhoo)" – While included in all of the Broadway productions,[48][50][51][52][52][53] it was cut from the original West End production after Alberta Hunter's show-stopping performance of the song caused jealousy among her co-stars.[54] It was sung in the prologue to the 1929 film version,[55] and performed instrumentally in the 1951 film.

- "Olio Dance" – Usually cut, as it was composed to cover a change of scenery; this orchestral piece partially uses the melody of "I Might Fall Back on You".[citation needed] The 1936 film substituted "Gallivantin' Around", performed as an olio by Irene Dunne (as Magnolia) in blackface.[citation needed] Some modern productions move the song "I Might Fall Back on You" to this spot.[citation needed]

- "You Are Love" – Included in all stage productions, and shorter versions were used in both the 1936 and the 1951 films.[citation needed]

- "Act I Finale" – This was shortened in the 1936 film. Its midsection, banjo-dominant, buck-and-wing dance theme became a repeating motif in the 1951 film, played onstage during the backstage miscegenation scene, and later as a soft-shoe dance for Cap'n Andy and granddaughter Kim.[citation needed]

- "At the Chicago World's Fair" – Used in all stage productions except for the Prince 1994 revival; an instrumental version was performed in the 1936 film.[citation needed]

- "Why Do I Love You?" – Used in all stage versions, the song was originally written as a duet for Magnolia and Ravenal but was re-shaped as a solo for Parthy in the 1994 Broadway revival.[citation needed] A reprise of the song sung by the adult Kim in act 2 has often been omitted or replaced subsequent to the original Broadway production. Songs used as replacements include "Dance Away the Night" and "Nobody Else But Me".[56] "Why Do I Love You?" was sung during the exit music to the 1929 film;[57] it was performed only as background music for the 1936 film[58] and was sung in the 1951 film version.

- "In Dahomey" – Cut from the score after the 1946 Broadway production and never revived as it is viewed as racially offensive and unnecessary to the plot. Sung at the Chicago World's Fair by a group of supposedly African natives who chant in a supposed African language before switching to English.[citation needed]

- "Goodbye, My Lady Love" – Used only in American productions and the 1936 film.[citation needed]

- "After the Ball" – Included in all stage productions and in both the 1936 and 1951 films.[citation needed]

- "Hey, Feller" – Used in the 1927 and 1932 Broadway productions but cut from the 1928 London production and the 1946 Broadway revival[56] and the Prince in the 1994 revival.[59] The song was sung in the prologue to the 1929 film.[55] Used as background score in the 1951 film during the opening post-credits scene.[citation needed]

Additional numbers sometimes included in films and revivals:

- "Mis'ry's Comin' Aroun" was published in the complete vocal score; fragments of it are heard in the score, notably in the original overture and the miscegenation scene.[60] It was included in the 1994 Harold Prince revival.[citation needed]

- "Let's Start the New Year" – Included in the 1989 Paper Mill Playhouse production.[citation needed]

- "Dance Away the Night" was written by Kern and Hammerstein for the 1928 West End production.[citation needed]

- "I Have the Room Above Her" was written by Kern and Hammerstein for Ravenal and Magnolia in the 1936 film. It was included in the 1994 Broadway revival.[citation needed]

- "Gallivantin' Around" was written by Kern and Hammerstein for Magnolia for the 1936 film.[citation needed]

- "Ah Still Suits Me" was written by Kern and Hammerstein for the 1936 film, sung by Joe and Queenie (Paul Robeson and Hattie McDaniel).[citation needed] Included in the 1989 Paper Mill Playhouse production.[61]

- "Nobody Else but Me" was written by Kern and Hammerstein for the 1946 Broadway revival. This was the last song Kern ever wrote; he died shortly before the revival opened.[62] In the 1971 London revival, the song was sung by Julie, in a new scene written for that production.[citation needed] It is was frequently heard in revivals until about the 1980s.[citation needed]

- "Dandies on Parade" is a dance number arranged for the 1994 Broadway production by David Krane, largely from Kern's music.[citation needed]

Characters and notable casts

[edit]| Character | Description | Original Broadway [48] | Original West End [63] | 1932 Broadway [50] | 1946 Broadway [51] | 1971 West End [64] | 1983 Broadway [52] | 1994 Broadway [53] | 1998 West End [65] | 2016 West End[66] | Other notable performers in long-running, major market productions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cap'n Andy Hawks | owner & captain of the Cotton Blossom show boat; Parthy Ann's husband & Magnolia's father |

Charles Winninger | Cedric Hardwicke | Charles Winninger | Ralph Dumke | Derek Royle | Donald O'Connor | John McMartin | George Grizzard | Malcolm Sinclair | David Wayne, Mickey Rooney, Eddie Bracken, Robert Morse |

| Magnolia Hawks | daughter of Parthy and Cap'n Andy; Kim's mother; marries Gaylord Ravenal | Norma Terris | Edith Day | Norma Terris | Jan Clayton | Lorna Dallas | Sheryl Woods | Rebecca Luker | Teri Hansen | Gina Beck | Irene Dunne, Barbara Cook |

| Gaylord Ravenal | handsome river-boat gambler; Kim's father; marries Magnolia | Howard Marsh | Howett Worster | Dennis King | Charles Fredericks | Andre Jobin | Ron Raines | Mark Jacoby | Hugh Panaro | Chris Peluso | Kevin Gray |

| Julie La Verne | leading lady of the troupe; Steve's wife | Helen Morgan | Marie Burke | Helen Morgan | Carol Bruce | Cleo Laine | Lonette McKee | Lonette McKee | Terry Burrell | Rebecca Trehearn | Constance Towers, Valarie Pettiford |

| Steve Baker | leading man of the Cotton Blossom; protective husband of Julie | Charles Ellis | Colin Clive | Charles Ellis | Robert Allen | John Larson | Wayne Turnage | Doug LaBrecque | Rob Lorey | Leo Roberts | |

| Parthenia Ann "Parthy" Hawks | stern wife of Cap'n Andy | Edna May Oliver | Viola Compton | Edna May Oliver | Ethel Owen | Pearl Hackney | Avril Gentles | Elaine Stritch | Carole Shelley | Lucy Briers | Margaret Hamilton, Cloris Leachman, Karen Morrow |

| Pete | tough engineer of the Cotton Blossom; tries to flirt with Julie | Bert Chapman | Fred Hearne | James Swift | Seldon Bennett | Brian Gidley | Glenn Martin | David Bryant | David Dollase | Ryan Pidgen | |

| Joe | dock worker on the boat; Queenie's husband | Jules Bledsoe | Paul Robeson | Paul Robeson | Kenneth Spencer | Thomas Carey | Bruce Hubbard | Michel Bell | Michel Bell | Emmanuel Kojo | William Warfield, Donnie Ray Albert |

| Queenie | cook on the Cotton Blossom; Joe's wife | Tess Gardella | Alberta Hunter | Tess Gardella | Helen Dowdy | Ena Cabayo | Karla Burns | Gretha Boston | Gretha Boston | Sandra Marvin | Hattie McDaniel |

| Frank Schultz | performer on the boat who plays villain characters; Ellie's husband | Sammy White | Leslie Sarony | Sammy White | Buddy Ebsen | Kenneth Nelson | Paul Keith | Joel Blum | Joel Blum | Danny Collins | |

| Ellie | singer and dancer in an act with husband Frank | Eva Puck | Dorothy Lena | Eva Puck | Collette Lyons | Jan Hunt | Paige O'Hara | Dorothy Stanley | Clare Leach | Alex Young | |

| Kim | daughter of Magnolia and Ravenal | Norma Terris | Helen Moore | Evelyn Eaton | Alyce Mace (Young Kim) / Jan Clayton (older Kim) |

Yvonne Peters | Tracy Paul (Young Kim) / Karen Culliver (older Kim) |

Larissa Auble (Young Kim) / Tammy Amerson (older Kim) |

Laura Schutter | Christina Bennington | |

| Windy McClain | pilot of the Cotton Blossom | A. Alan Campbell | Jack Martin | A. Alan Campbell | Scott Moore | Len Maley | Richard Dix | Ralph Williams | Vince Metcalfe | Adam Dutton |

Production history

[edit]Original 1927 production

[edit]

Ziegfeld previewed the show in a pre-Broadway tour from November 15 to December 19, 1927. The locations included the National Theatre in Washington, D.C., the Nixon Theatre in Pittsburgh, the Ohio Theatre in Cleveland, and the Erlanger Theatre in Philadelphia.[67][68] The show opened on Broadway at the Ziegfeld Theatre on December 27, 1927. The critics were immediately enthusiastic, and the show was a great popular success, running a year and a half, for a total of 572 performances.[69]

The production's direction was credited to Zeke Colvan at the time it premiered, but Oscar Hammerstein II, who remained uncredited, was also responsible for much of the show's staging.[48][b] Choreography for the show was by Sammy Lee. The original cast included Norma Terris as Magnolia Hawks and her daughter Kim (as an adult), Howard Marsh as Gaylord Ravenal, Helen Morgan as Julie LaVerne, Jules Bledsoe as Joe, Charles Winninger as Cap'n Andy Hawks, Edna May Oliver as Parthy Hawks, Sammy White as Frank Schultz, Eva Puck as Ellie May Chipley, and Tess Gardella as Queenie. The orchestrator was Robert Russell Bennett, and the conductor was Victor Baravalle. The scenic design for the original production was by Joseph Urban, who had worked with Ziegfeld for many years in his Follies and had designed the elaborate new Ziegfeld Theatre itself. Costumes were designed by John Harkrider.[48]

In his opening night review for The New York Times, Brooks Atkinson called the book's adaptation "intelligently made", and the production one of "unimpeachable skill and taste". He termed Terris "a revelation"; Winninger "extraordinarily persuasive and convincing"; and Bledsoe's singing "remarkably effective".[70]

Paul Robeson

[edit]The character Joe, the stevedore who sings "Ol' Man River", was expanded from the novel and written specifically by Kern and Hammerstein for Paul Robeson, already a noted actor and singer. Although he is the actor most identified with the role and the song, he was unavailable for the original production due to its opening delay. Jules Bledsoe premiered the part. Robeson played Joe in four notable productions of Show Boat: the 1928 London premiere production, the 1932 Broadway revival, the 1936 film version and a 1940 stage revival in Los Angeles.

Reviewing the 1932 Broadway revival, the critic Brooks Atkinson described Robeson's performance: "Mr. Robeson has a touch of genius. It is not merely his voice, which is one of the richest organs on the stage. It is his understanding that gives 'Old Man River' an epic lift. When he sings ... you realize that Jerome Kern's spiritual has reached its final expression."[71]

North American revivals

[edit]

After closing at the Ziegfeld Theatre in 1929, the original production toured extensively. The national company is notable for including Irene Dunne as Magnolia. Hattie McDaniel played Queenie in a 1933 West Coast production, joined by tenor Allan Jones as Ravenal.[72] Show Boat was revived by Ziegfeld on Broadway in 1932 at the Casino Theatre with most of the original cast, but with Paul Robeson as Joe and Dennis King as Ravenal.[73]

In 1946, a major new Broadway revival was produced by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II at the show's original home, the Ziegfeld Theatre. The 1946 revival featured a revised score and new song by Kern and Hammerstein, and a new overture and orchestrations by Robert Russell Bennett. The show was directed by Hammerstein and Hassard Short and featured Jan Clayton (Magnolia), Charles Fredricks (Ravenal), Carol Bruce (Julie), Kenneth Spencer (Joe), Helen Dowdy (Queenie), and Buddy Ebsen (Frank). Kern died just weeks before the January 5, 1946 opening, making it the last show he worked on. The production ran for 418 performances and then toured extensively. Its cost was reportedly $300,000, and a month before the Broadway closing, it was reported as still $130,000 from breaking even.[74]

Additional New York revivals were produced in 1948 and 1954 at the New York City Center with the 1948 production starred Billy House as Cap'n Andy.[75] The 1954 production was mounted by the New York City Opera with Burl Ives (Cap'n Andy), Laurel Hurley (Magnolia), Robert Rounseville (Ravenal), Helena Bliss (Julie), Marjorie Gateson (Parthy), Boris Aplon (Pete), Lawrence Winters (Joe), and Helen Phillips (Queenie) [76] The Music Theatre of Lincoln Center company produced Show Boat in 1966 at the New York State Theater in a new production. It starred Barbara Cook (Magnolia), Constance Towers (Julie), Stephen Douglass (Ravenal), David Wayne (Cap'n Andy), Margaret Hamilton (Parthy) and William Warfield (Joe).[77] It was produced by Richard Rodgers, and Robert Russell Bennett once again provided a new overture and revised orchestrations.[78]

The Houston Grand Opera staged a revival of Show Boat that premiered at Jones Hall in Houston in June 1982 and then toured to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles, the Orpheum Theatre in San Francisco, the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C., and finally to the Gershwin Theatre on Broadway in 1983.[79][80][81] The production also toured overseas to the Cairo Opera House in Egypt.[80] The show was produced by Robert A. Buckley and Douglas Urbanski. Mickey Rooney portrayed Cap'n Andy for portions of the tour, but Donald O'Connor took over the role on Broadway. Lonette McKee (Julie) and Karla Burns (Queenie), and director Michael Kahn all received Tony Award nominations for their work.[82] Other cast members included Ron Raines (Gaylord Ravenal), Sheryl Woods (Magnolia), Avril Gentles (Parthy), Bruce Hubbard (Joe), and Paige O'Hara (Ellie).[79]

In 1989, the Paper Mill Playhouse of Millburn, New Jersey, mounted a production which was noted for its intention to restore the show in accordance with the creators' original intentions. The production restored part of the original 1927 overture and one number discarded from the show after the Broadway opening, as well as the song Ah Still Suits Me, written by Kern and Hammerstein for the 1936 film version. It was directed by Robert Johanson and starred Eddie Bracken as Cap'n Andy. The Paper Mill production was preserved on videotape and broadcast on PBS.[61]

Toronto (1993, later Broadway)

[edit]Livent Inc. produced Show Boat in Toronto in 1993, starring Rebecca Luker as Magnolia, Mark Jacoby as Ravenal, Lonette McKee as Julie, Robert Morse as Cap'n Andy, Elaine Stritch as Parthy, Michel Bell as Joe and Gretha Boston as Queenie. Co-produced and directed by Harold Prince and choreographed by Susan Stroman, closing in June 1995.[citation needed] A Broadway production opened at the George Gershwin Theatre on October 2, 1994, and continued for 947 performances making it Broadway's longest-running Show Boat to date.[53] It starred most of the Toronto cast, but with John McMartin as Cap'n Andy. Robert Morse remained in the Toronto cast and was joined by Cloris Leachman as Parthy, Patti Cohenour as Magnolia, Hugh Panaro as Ravenal, and Valerie Pettiford as Julie.

The production departed from previous iterations by tightening the book, dropping or adding songs used in or cut from various productions, and highlighting its racial elements. Prince transformed "Why Do I Love You?" from a duet between Magnolia and Ravenal to a lullaby sung by Parthy to Magnolia's baby girl, and then reprised as an up-tempo production number finale. The love duet for Magnolia and Ravenal, "I Have the Room Above Her", written by Kern and Hammerstein for the 1936 film, was added to the production. Two new mime and dance "Montages" in Act 2 depicted the passage of time through changing styles of dance and music.[83] The production went on tour, playing at the Kennedy Center, and it was staged in London (1998) and Melbourne, Australia.[citation needed]

London productions

[edit]The original London West End production of Show Boat opened May 3, 1928, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane and featured among the cast, Cedric Hardwicke as Capt. Andy, Edith Day as Magnolia, Paul Robeson as Joe, and Alberta Hunter as Queenie.[63] Mabel Mercer, later famed as a cabaret singer, was in the chorus. Other West End presentations include a 1971 production at the Adelphi Theatre, which ran for 909 performances. Derek Royle was Cap'n Andy, Cleo Laine was Julie, and Pearl Hackney played Parthy Ann.[68]

The Hal Prince production ran at the Prince Edward Theatre in 1998,[84] and was nominated for the Olivier Award, Outstanding Musical Production (1999).[85] Other notable revivals in England have included the joint Opera North/Royal Shakespeare Company production of 1989,[67] which ran at the London Palladium in 1990, and the 2006 production directed by Francesca Zambello, presented by Raymond Gubbay at London's Royal Albert Hall. It was the first fully staged musical production in the history of that venue.[86] Karla Burns, who had appeared as Queenie in the 1983 Broadway revival, reprised the role for the Opera North and RSC production, becoming the first black performer to win the Laurence Olivier Award.[80]

A production was transferred from Sheffield's Crucible Theatre to London's New London Theatre with previews beginning on April 9, 2016, and an official opening on April 25, 2016. It was directed by Daniel Evans using the Goodspeed Musicals version of the show. The cast included Gina Beck as Magnolia, Lucy Briers as Parthy Ann and Malcolm Sinclair as Cap'n Andy.[87][88] Despite very favorable reviews, the show closed at the end of August 2016.[89]

Adaptations

[edit]Film and television

[edit]Show Boat has been adapted for film three times, and for television once.

- 1929 Show Boat. Universal. Released in silent and partial sound versions. Not a film version of the musical; its plot is based on the original Edna Ferber novel. Immediately after the silent film was completed, a prologue with some music from the show was filmed and added to a part-talkie version of the same film, which was released with two sound sequences.

- 1936 Show Boat. Universal. Directed by James Whale. A mostly faithful film version of the show, featuring four members of the original Broadway cast, as well as Irene Dunne, who had appeared in the national tour. Other cast members from stage productions included Jones as Ravenal, McDaniel as Queenie, Robeson as Joe, Winninger as Cap'n Andy, Morgan as Julie and White as Frank.[90] Screenplay by Oscar Hammerstein II; music arrangements by Robert Russell Bennett; music direction and conducting by Victor Baraville.

- 1946 Till the Clouds Roll By. MGM. In this fictionalized film biography of composer Jerome Kern (played by Robert Walker), Show Boat's 1927 opening night on Broadway is depicted in a lavishly staged fifteen-minute medley of six of the show's songs. The number features Kathryn Grayson, Tony Martin, Lena Horne, Virginia O'Brien, Caleb Peterson, and William Halligan as, respectively, Magnolia, Ravenal, Julie, Ellie, Joe, and Cap'n Andy.

- 1951 Show Boat. MGM. Somewhat revised Technicolor film version. Follows the basic storyline and contains many songs from the show but makes many changes in the details of plot and character. The most financially successful and frequently revived of the three film versions.

- 1989 A live performance by the Paper Mill Playhouse was videotaped for television and shown on Great Performances on PBS. It contains more of the songs (and fewer cuts) than any of the film versions. It includes the choral number "Let's Start the New Year", which was dropped from the show before its Broadway opening, and "Ah Still Suits Me", a song written by Kern and Hammerstein for the 1936 film version of the show.[61]

Radio

[edit]Show Boat was adapted for live radio at least seven times. Due to network censorship rules, many of the radio productions eliminated the miscegenation aspect of the plot. Notable exceptions were the 1940 Cavalcade of America broadcast and the 1952 Lux Radio Theatre broadcast.[91]

- The Campbell Playhouse (CBS Radio, March 31, 1939). Directed and introduced by Orson Welles. This was a non-musical version of the story that was based more closely on Ferber's novel than on the musical. From the original stage cast Helen Morgan repeated her portrayal of Julie, here singing one song not from the musical. Welles portrayed Cap'n Andy, Margaret Sullavan was Magnolia, and author Edna Ferber made her acting debut as Parthy. This version made Julie into an illegal alien who must be deported.

- Cavalcade of America (NBC Radio, May 28, 1940). A half-hour dramatization with Jeanette Nolan, John McIntire, Agnes Moorehead and the Ken Christy Chorus. Although brief, it was remarkably faithful to the original show.

- Lux Radio Theatre (CBS, June 1940). Introduced and produced by Cecil B. DeMille, it featured Irene Dunne, Allan Jones, and Charles Winninger, all of whom were in the 1936 film version. In this condensed version some songs from the show were sung, but Julie was played by a non-singing Gloria Holden. This version made the biracial Julie a single woman. Only a few lines of Ol' Man River were heard, sung by a chorus. While supposedly based on the 1936 film, this production used the ending of the original show, which the film did not use.[citation needed]

- Radio Hall of Fame (1944). This production featured Kathryn Grayson, playing Magnolia for the first time.[68] Also in the cast were Allan Jones as Ravenal, Helen Forrest as Julie, Charles Winninger as Cap'n Andy, Ernest Whitman as Joe, and Elvia Allman as Parthy.

- The Railroad Hour (ABC Radio, 1950). Condensed to a half-hour, this version featured singers Dorothy Kirsten, Gordon MacRae, and Lucille Norman. "Ol' Man River" was sung by MacRae instead of by an African-American singer. Explanation of Julie and Steve's departure went completely unmentioned in this version.[citation needed]

- Lux Radio Theatre (CBS, February 11, 1952). A radio version of the 1951 MGM film featuring Kathryn Grayson, Ava Gardner, Howard Keel, and William Warfield from the film's cast. Jay C. Flippen portrayed Cap'n Andy. This version was extremely faithful to the 1951 film adaptation.[91]

- In 2011, a two-part version was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in the Classic Serial spot. Solely based on the novel by Edna Ferber, it was dramatized by Moya O'Shea, and was produced and directed by Tracey Neale. It starred Samantha Spiro as Magnolia, Ryan McCluskey as Ravenal, Nonso Anozie as Joe, Tracy Ifeachor as Queenie, Laurel Lefkow as Parthy, Morgan Deare as Cap'n Andy and Lysette Anthony as Kim. Original music was by Neil Brand.[92]

- On June 16, 2012, a revival of the musical by Lyric Opera of Chicago was broadcast by WFMT-Radio of Chicago.[93] This production of Show Boat reinstated the songs Mis'ry's Comin' Round, Till Good Luck Comes My Way and Hey, Feller! It marked the first time a virtually complete version of Show Boat had ever been broadcast on radio.[citation needed]

Concert hall

[edit]- On December 29, 1941, the Cleveland Orchestra, under the direction of Artur Rodziński, premiered and recorded the orchestral work Show Boat: A Scenario for Orchestra which was crafted by Kern.[94] A 22-minute orchestral work weaving together themes from the show,[95] it was later recorded by John Mauceri and the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra on the 1996 album The Hollywood Bowl on Broadway.[96]

Selected recordings

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

- 1928 – original London cast album, with the show's original orchestrations. This was released in England on 78 rpm records years before being sold in the United States. As the U.S. had not yet begun making original cast albums of Broadway shows, the 1927 Broadway cast as a whole was never recorded performing the songs, although Jules Bledsoe, Helen Morgan, and Tess Gardella did record individual numbers from it. The cast on the 1928 London album included Edith Day, Howett Worster, Marie Burke and Alberta Hunter. Due to contractual restrictions, cast member Paul Robeson was replaced on the album as Joe by his understudy, baritone Norris Smith. But that same year, Robeson, with the same chorus that accompanied him in the show, did record "Ol' Man River" in its original orchestration. That recording was later released separately. His rendition appears on the EMI CD "Paul Robeson Sings 'Ol' Man River' and Other Favorites".

- 1932 – studio cast recording on 78rpm by Brunswick Records. Later re-released by Columbia Records on 78rpm, 33-1/3rpm and briefly on CD. This recording featured Helen Morgan, Paul Robeson, James Melton, Frank Munn, and Countess Olga Albani, and was issued in conjunction with the 1932 revival of the show, although it was not strictly an "original cast" album of that revival. The orchestra was conducted by Victor Young, and the original orchestrations and vocal arrangements were not used.

- 1946 – Broadway revival cast recording. Issued on 78rpm, LP and CD. The 78-RPM and LP versions were issued by Columbia, the CD by Sony. This was the first American recording of Show Boat which used the cast, conductor, and orchestrations of a major Broadway revival of the show. (Robert Russell Bennett's orchestrations for this revival thoroughly modified his original 1927 orchestrations.) Jan Clayton, Carol Bruce, Charles Fredericks, Kenneth Spencer, and Collette Lyons were featured. Buddy Ebsen also appeared in the revival, but not on the album. Includes the new song "Nobody Else But Me".

- 1951 – MGM Records soundtrack album, with cast members of the 1951 film version. The first film soundtrack of Show Boat to be issued on records. Appeared both on 45rpm and 33-1/3rpm, later on CD in a much expanded edition. Actress Ava Gardner, whose singing voice was replaced by Annette Warren's in the film, is heard singing on this album. The expanded version on CD contains both Warren's and Gardner's vocal tracks. This marked the recording debut of William Warfield, who played Joe and sang "Ol' Man River" in the film. Orchestrations were by Conrad Salinger, Robert Franklyn, and Alexander Courage.

- 1956 – RCA Victor studio cast album conducted by Lehman Engel. This album featured more of the score on one LP than had been previously recorded. It featured a white singer, famed American baritone Robert Merrill, as both Joe and Gaylord Ravenal. Other singers included Patrice Munsel as Magnolia and Rise Stevens as Julie. Issued on CD in 2009, but omitting Frank and Ellie's numbers, which had been sung on the LP version by Janet Pavek and Kevin Scott. The original orchestrations were not used.

- 1958 – RCA Victor studio cast album. The first Show Boat in stereo, this recording starred Howard Keel (singing "Ol' Man River" as well as Gaylord Ravenal's songs), Anne Jeffreys, and Gogi Grant, and did not use the original orchestrations. It was issued on CD in 2010.

- 1959 – EMI British studio cast album. It featured Marlys Walters as Magnolia, Don McKay as Ravenal, Shirley Bassey as Julie, Dora Bryan as Ellie, and Inia Te Wiata singing "Ol' Man River".

- 1962 – Columbia studio cast album. Starring Barbara Cook, John Raitt, Anita Darian, and William Warfield, this was the first "Show Boat" recording issued on CD. Although Robert Russell Bennett was uncredited, this used several of his orchestrations for the 1946 revival of the show, together with some modifications.

- 1966 – Lincoln Center cast album. Issued by RCA Victor, it featured Cook, Constance Towers, Stephen Douglass, and William Warfield. Robert Russell Bennett's orchestrations were modified even further. Also available on CD.

- 1971 – London revival cast album. Jazz singer Cleo Laine, soprano Lorna Dallas, tenor Andre Jobin, and bass-baritone Thomas Carey were the leads. It used completely new orchestrations bearing almost no resemblance to Robert Russell Bennett's. This was the first 2-LP album of Show Boat. It included more of the score than had been previously put on records. Issued later on CD.

- 1987 – complete EMI studio recording. This is a three-CD set which, for the first time, is of the entire score, with the authentic 1927 orchestrations, uncensored lyrics, and vocal arrangements. The cast includes Frederica von Stade, Jerry Hadley, Teresa Stratas, Karla Burns, Bruce Hubbard, David Garrison and Paige O'Hara, conducted by John McGlinn.

- 1993 – Toronto revival cast recording, with the same cast as the 1994 Broadway production.

There have been many other studio cast recordings of Show Boat in addition to those mentioned above. The soundtrack of the 1936 film version has appeared on a so-called "bootleg" CD label called Xeno.[97]

Racial issues

[edit]Integration

[edit]Show Boat boldly portrayed racial issues and was the first racially integrated musical, in that both black and white performers appeared and sang on stage together. [c] Ziegfeld's Follies featured solo African American performers such as Bert Williams, but would not have included a black woman in the chorus.[citation needed] Show Boat was structured with two choruses – a black chorus and a white chorus.[98] Ethnomusicologist Richard Keeling noted that "Hammerstein uses the African-American chorus as essentially a Greek chorus, providing clear commentary on the proceedings, whereas the white choruses sing of the not-quite-real."[99] In Show Boat Jerome Kern used the AABA-chorus form exclusively in songs sung by African-American characters ("Ol' Man River", "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man"), a form that later would be regarded as typical of "white" popular music.[100]

Show Boat was the first Broadway musical to seriously depict an interracial marriage, as in Ferber's original novel, and to feature a character of mixed race who was "passing" for white.

Language and stereotypes

[edit]The word "nigger"

[edit]The show has generated controversy for the subject matter of interracial marriage, the historical portrayal of blacks working as laborers and servants in the 19th-century South, and the use of the word niggers in the lyrics (this is the first word in the opening chorus of the show). Originally the show opened with the black chorus onstage singing:

- Niggers all work on the Mississippi,

- Niggers all work while the white folks play.

- Loadin' up boats wid de bales of cotton,

- Gittin' no rest till de Judgment Day.[101]

In subsequent productions, "niggers" has been changed to "colored folk", to "darkies", and in one choice, "Here we all", as in "Here we all work on the Mississippi. Here we all work while the white folks play." In the 1966 Lincoln Center production of the show, produced two years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, this section of the opening chorus was omitted rather than having words changed. The 1971 London revival used "Here we all work on the Mississippi". The 1988 CD for EMI restored the original 1927 lyric, while the Harold Prince revival chose "colored folk".[102][103] The Paper Mill Playhouse production, videotaped and telecast by PBS in 1989, used the word "nigger" when said by an unsympathetic character, but otherwise used the word "Negro".

Many critics believe that Kern and Hammerstein wrote the opening chorus to give a sympathetic voice to an oppressed people, and that they intended its use in an ironic way, as it had so often been used in a derogatory way. They wanted to alert the audience to the realities of racism:

'Show Boat begins with the singing of that most reprehensible word – nigger – yet this is no coon song... [it] immediately establishes race as one of the central themes of the play. This is a protest song, more ironic than angry perhaps, but a protest nonetheless. In the singers' hands, the word nigger has a sardonic tone... in the very opening, Hammerstein has established the gulf between the races, the privilege accorded the white folks and denied the black, and a flavor of the contempt built into the very language that whites used about African Americans. This is a very effective scene.... These are not caricature roles; they are wise, if uneducated, people capable of seeing and feeling more than some of the white folk around them.[99]

The racial situations in the play provoke thoughts of how hard it must have been to be black in the South. In the dialogue, some of the blacks are called "niggers" by the white characters in the story. (Contrary to what is sometimes thought, black slavery is not depicted in the play; U.S. slavery was abolished by 1865, and the story runs from the 1880s to the late 1920s.) At first, it is shocking to believe they are allowed to use a word that negative at all in a play... But in the context in which it is used, it is appropriate due to the impact it makes. It reinforces how much of a derogatory term "nigger" was then and still is today.[104]

The word has not been used in any of the film versions of the musical. In the show, the sheriff refers to Steve and Julie as having "nigger blood." In the 1936 and 1951 film versions, this was changed to "Negro blood". Likewise, the unsympathetic Pete calls Queenie a "nigger" in the stage version but refers to her as "colored" in the 1936 film, and does not use either word in the 1951 film.

African-American English

[edit]Those who consider Show Boat racially insensitive often note that the dialogue and lyrics of the black characters (especially the stevedore Joe and his wife Queenie) and choruses use various forms of African American Vernacular English. An example of this is shown in the following text:

- Hey!

- Where yo' think you're goin'?

- Don't yo' know dis show is startin' soon?

- Hey!

- Jes' a few seats left yere!

- It's light inside an' outside dere's no moon

- What fo' you gals dressed up dicty?

- Where's yo' all gwine?

- Tell dose stingy men o' yourn

- To step up here in line![105]

Whether or not such language is an accurate reflection of the vernacular of black people in Mississippi at the time, the effect of its usage has offended some critics, who see it as perpetuating racial stereotypes.[106] The character Queenie (who sings the above verses) in the original production was played not by an African American but by the Italian-American actress Tess Gardella in blackface (Gardella was perhaps best known for portraying Aunt Jemima in blackface).[107] Attempts by non-black writers to imitate black language stereotypically in songs such as "Ol' Man River" were alleged to be offensive, a claim that was repeated eight years later by critics of Porgy and Bess.[108] However, such critics sometimes acknowledged that Hammerstein's intentions were noble, since "'Ol' Man River' was the song in which he first found his lyrical voice, compressing the suffering, resignation, and anger of an entire race into 24 taut lines and doing it so naturally that it's no wonder folks assume the song's a Negro spiritual."[109]

The theatre critics and veterans Richard Eyre and Nicholas Wright believe that Show Boat was revolutionary, not only because it was a radical departure from the previous style of plotless revues, but because it was a show by non-black writers that portrayed black people sympathetically rather than condescendingly:

Instead of a line of chorus girls showing their legs in the opening number singing that they were happy, happy, happy, the curtain rose on black dock-hands lifting bales of cotton and singing about the hardness of their lives. Here was a musical that showed poverty, suffering, bitterness, racial prejudice, a sexual relationship between black and white, a love story which ended unhappily – and of course show business. In "Ol' Man River" the black race was given an anthem to honor its misery that had the authority of an authentic spiritual.[110]

Revisions and cancellations

[edit]Since the musical's 1927 premiere, Show Boat has both been condemned as a prejudiced show based on racial caricatures and championed as a breakthrough work that opened the door for public discourse in the arts about racism in America. Some productions (including one planned for June 2002 in Connecticut) have been cancelled because of objections.[111] Such cancellations have been criticized by supporters of the arts. After planned performances in 1999 by an amateur company in Middlesbrough, England, where "the show would entail white actors 'blacking up'" were "stopped because [they] would be 'distasteful' to ethnic minorities", the critic for a local newspaper declared that the cancellation was "surely taking political correctness too far. … [T]he kind of censorship we've been talking about – for censorship it is – actually militates against a truly integrated society, for it emphasizes differences. It puts a wall around groups within society, dividing people by creating metaphorical ghettos, and prevents mutual understanding".[112]

As attitudes toward race relations have changed, producers and directors have altered some content to make the musical more "politically correct": "Show Boat, more than many musicals, was subject to cuts and revisions within a handful of years after its first performance, all of which altered the dramatic balance of the play."[99]

1993 revival

[edit]The 1993 Hal Prince revival, originating in Toronto, was deliberately staged to cast attention on racial disparities; throughout the production, African-American actors constantly cleaned up messes, appeared to move the sets (even when hydraulics actually moved them), and performed other menial tasks.[113] After a New Year's Eve ball, all the streamers fell on the floor and African Americans immediately began sweeping them away. A montage in the second act showed time passing using the revolving door of the Palmer House in Chicago, with newspaper headlines being shown in quick succession, and snippets of slow motion to highlight a specific moment, accompanied by brief snippets of Ol' Man River. African-American dancers were seen performing a specific dance, and this would change to a scene showing white dancers performing the same dance. This was meant to illustrate how white performers "appropriated" the music and dancing styles of African Americans. Earlier productions of Show Boat, even the 1927 stage original and the 1936 film version, did not go this far in social commentary.[114]

During the Toronto production, many black community leaders and their supporters expressed opposition to the show, protesting in front of the theatre, "shouting insults and waving placards reading Show Boat Spreads Lies and Hate and Show Boat = Cultural Genocide".[115] Various theatre critics in New York, however, commented that Prince highlighted racial inequality in his production to show its injustice, as well as to show the historical suffering of blacks. A critic noted that he included "an absolutely beautiful piece of music cut from the original production and from the movie ["Mis'ry's Comin' Round"] ... a haunting gospel melody sung by the black chorus. The addition of this number is so successful because it salutes the dignity and the pure talent of the black workers and allows them to shine for a brief moment on the center stage of the showboat".[113]

Analysis

[edit]Many commentators, both black and non-black, view the show as an outdated and stereotypical commentary on race relations that portrays blacks in a negative or inferior position. Douglass K. Daniel of Kansas State University has commented that it is a "racially flawed story",[116] and the African-Canadian writer M. NourbeSe Philip claims:

The affront at the heart of Show Boat is still very alive today. It begins with the book and its negative and one-dimensional images of Black people and continues on through the colossal and deliberate omission of the Black experience, including the pain of a people traumatized by four centuries of attempted genocide and exploitation. Not to mention the appropriation of Black music for the profit of the very people who oppressed Blacks and Africans. All this continues to offend deeply. The ol' man river of racism continues to run through the history of these productions and is very much part of this (Toronto) production. It is part of the overwhelming need of white Americans and white Canadians to convince themselves of our inferiority – that our demands don't represent a challenge to them, their privilege and their superiority.[106]

Supporters of the musical believe that the depictions of racism should be regarded not as stereotyping blacks but rather satirizing the common national attitudes that both held those stereotypes and reinforced them through discrimination. In the words of The New Yorker theatre critic John Lahr:

Describing racism doesn't make Show Boat racist. The production is meticulous in honoring the influence of black culture not just in the making of the nation's wealth but, through music, in the making of its modern spirit.[1]

As described by Joe Bob Briggs:

Those who attempt to understand works like Show Boat and Porgy and Bess through the eyes of their creators usually consider that the show "was a statement AGAINST racism. That was the point of Edna Ferber's novel. That was the point of the show. That's how Oscar wrote it...I think this is about as far from racism as you can get."[117]

According to Rabbi Alan Berg, Kern and Hammerstein's score to Show Boat is "a tremendous expression of the ethics of tolerance and compassion".[118] As Harold Prince (not Kern, to whom the quote has been mistakenly attributed) states in the production notes to his 1993 production of the show:

Throughout pre-production and rehearsal, I was committed to eliminate any inadvertent stereotype in the original material, dialogue which may seem "Uncle Tom" today... However, I was determined not to rewrite history. The fact that during the 45-year period depicted in our musical there were lynchings, imprisonment, and forced labor of the blacks in the United States is irrefutable. Indeed, the United States still cannot hold its head high with regard to racism.

Oscar Hammerstein's commitment to idealizing and encouraging tolerance theatrically started with his libretto to Show Boat. It can be seen in his later works, many of which were set to music by Richard Rodgers.[119] Carmen Jones is an attempt to present a modern version of the classic French opera through the experiences of African Americans during wartime, and South Pacific explores interracial marriage and prejudice. Finally, The King and I deals with different cultures' preconceived notions regarding each other and the possibility for cultural inclusiveness in societies.

Regarding the original author of Show Boat, Ann Shapiro states that

Edna Ferber was taunted for being Jewish; as a young woman eager to launch her career as a journalist, she was told that the Chicago Tribune did not hire women reporters. Despite her experience of antisemitism and sexism, she idealized America, creating in her novels an American myth where strong women and downtrodden men of any race prevail... [Show Boat] create[s] visions of racial harmony... in a fictional world that purported to be America but was more illusion than reality. Characters in Ferber's novels achieve assimilation and acceptance that was periodically denied Ferber herself throughout her life.[120]

Whether or not the show is racist, many contend that productions of it should continue as it serves as a history lesson of American race relations. According to African-American opera singer Phillip Boykin, who played the role of Joe in a 2000 tour,

Whenever a show deals with race issues, it gives the audience sweaty palms. I agree with putting it on the stage and making the audience think about it. We see where we came from so we don't repeat it, though we still have a long way to go. A lot of history would disappear if the show was put away forever. An artist must be true to an era. I'm happy with it.[121]

References and Notes

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Ferber's novel spells the character's name Jo. The spelling was changed to Joe in the musical.

- ^ Zeke Colvan was officially credited as director of the production, but in his 1977 book Show Boat: The History of a Classic American Musical, musical historian Miles Kreuger says that when he interviewed Oscar Hammerstein II months before the latter's death, the always modest Hammerstein admitted that now that Colvan was dead, he could finally state that it was he (Hammerstein) who had directed the original production of the show, and that Colvan had actually served as stage manager.[citation needed]

- ^ Despite its technical correctness, that Show Boat deserves this title has been disputed by some. See note No. 5 and corresponding text.[clarification needed]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Lahr, John (October 27, 1993). "Mississippi Mud". The New Yorker. pp. 123–126.

- ^ Lubbock 1962, Chapter, "American Musical Theatre: An Introduction".

- ^ Naden 2011, p. 16.

- ^ Wood 2019, p. 113.

- ^ Block 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Wood 2019, pp. 105, 108.

- ^ Kreuger 1977, p. 12.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Decker 2013, pp. 1–24.

- ^ Wood 2019, pp. 107–110.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Decker 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Gilbert 1999, p. 370.

- ^ a b c Dudley 2010, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d Meade 2005, p. 136.

- ^ Oster & Vermeil 2008, Chapter, "Kern: Show Boat Mississippi".

- ^ a b c d e f g Letellier 2015, p. 1066.

- ^ Decker 2013, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 248.

- ^ Decker 2013, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 14.

- ^ a b Decker 2013, pp. 1–23.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 23.

- ^ Decker 2013, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Decker 2013, pp. 22–24.

- ^ a b Decker 2013, p. 24.

- ^ Wood 2019, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Jones, John Bush 2003, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Wood & 2019 109.

- ^ a b Jones, John Bush 2003, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 25.

- ^ Block 1997, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Kenrick 2010, p. 202.

- ^ Wood 2019, p. 131.

- ^ Wood 2019, p. 133.

- ^ Wood 2019, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Peyser 2006, p. 151.

- ^ Ginell 2022, p. 80.

- ^ a b Ginell 2022, p. 81.

- ^ Wood 2019, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 29-30.

- ^ Wood 2019, p. 132.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 30.

- ^ Kantor & Maslon 2004, pp. 112–19.

- ^ Jones 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Decker 2013, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Bloom & Vlastnik 2004, pp. 290–293.

- ^ a b c d e Dietz 2019, p. 430-431.

- ^ Graziano 2017, p. 129.

- ^ a b Dietz 2018, p. 201-202.

- ^ a b Dietz 2015, p. 312-313.

- ^ a b c Dietz 2016a, pp. 171–172.

- ^ a b c Dietz 2016b, pp. 171–172.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 129.

- ^ a b Barrios 1995, p. 90.

- ^ a b Block 1997, p. W37-W41.

- ^ Mordden 2015, p. 34.

- ^ Block 2023, p. 32.

- ^ Lewis 2015, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Block 1997, pp. 22–24.

- ^ a b c Klein, Alvin (June 11, 1989). "Theater; A 'Show Boat' as It's Meant to Be". The New York Times.

- ^ "Album Review: Show Boat 1946 Broadway Revival Cast". Answers.com. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Wearing 2014, p. 590.

- ^ Kreuger 1977, p. 205.

- ^ "Show Boat: London Production (1998)". ovrtur.com. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ Cheesman, Neil (September 4, 2015). "Full casting announced for Sheffield Theatre's SHOW BOAT". London Theatre.

- ^ a b Vancheri, Barbara. "'Show Boat' continues successful voyage". Post-Gazette, August 23, 1998. Retrieved January 6, 2006.

- ^ a b c Kreuger 1977, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Dietz 2019, p. 430.

- ^ Atkinson, J. Brooks (December 28, 1927). "Show Boat". The New York Times.

- ^ Atkinson, J. Brooks (May 20, 1932). "THE PLAY; Show Boat" as Good as New". The New York Times.

- ^ "Show Boat", Criterion Collection. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- ^ Dietz 2018, pp. 201–202.

- ^ "Show Boat 130G Red After Nearly a Year; Will Fold on Jan. 4", Variety, December 4, 1946, p. 49

- ^ Dietz 2015, p. 448.

- ^ Dietz 2014, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Block 1997, p. 310.

- ^ Kreuger 1977, p. 201.

- ^ a b Victor Gluck (Aug 27, 1982). "B 'way Recycles Classic Wares". Back Stage. 23 (35): 39–40, 42, 44.

- ^ a b c Decker 2013, Chapter, "Queenie’s Laugh, 1966–1998".

- ^ "Legitimate: Show Out Of Town – Show Boat". Variety. 307 (9): 84. June 30, 1982.

- ^ Morrow 1987, p. 257.

- ^ Barbara Isenberg (October 9, 1994). "Prince at the Helm". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 215.

- ^ Letellier 2015, p. 1068.

- ^ Dowden, Neil (June 6, 2006). "Show Boat at Royal Albert Hall". OMH. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- ^ "West End transfer for critically acclaimed Show Boat", Best of Theatre, February 11, 2016.

- ^ Billington, Michael. "Show Boat: the classic musical still shipshape after all these years", The Guardian, April 26, 2016.

- ^ "Despite five-star reviews, Show Boat closes five months early on 27 Aug", StageFaves.com, May 10, 2016.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 257.

- ^ a b Kreuger 1977, p. 234.

- ^ "'Show Boat', Episode 1 of 2, 20 Feb 2011 and 26 Feb 2011" bbc.co.uk. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ^ "The Bucksbaum Family Lyric Opera Broadcasts - Lyric Opera of Chicago". Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-16.

- ^ Rosenberg 2000, p. 182, 661.

- ^ "Kern: Show Boat – A Scenario for Orchestra", Archive.org. Retrieved October 16, 2021

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "The Hollywood Bowl on Broadway Review". AllMusic. Retrieved November 6, 2024.

- ^ "Show Boat (1936 Soundtrack)". AllMusic. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ Decker 2013, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Keeling, Richard (a.k.a. musickna) (December 8, 2005). Music – "Show Boat". Blogger.com. Retrieved January 2, 2006.

- ^ Appen, Ralf von / Frei-Hauenschild, Markus "AABA, Refrain, Chorus, Bridge, Prechorus — Song Forms and their Historical Development". In: Ralf von Appen (ed.), Samples. Online Publikationen der Gesellschaft für Popularmusikforschung/German Society for Popular Music Studies e.V. André Doehring and Thomas Phleps. Vol. 13 (2015), pp. 14–15.

- ^ Asch 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Christoph, Ella; Polkow, Dennis (February 15, 2012). "Life Upon the Wicked Stage: Director Francesca Zambello on why "Show Boat" remains relevant". New City Stage. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (August 20, 1991). "'Show Boat' Just Keeps Rolling Along". The Times Daily.

- ^ Cronin, Patricia (June 1997). ""Timeless 'Show Boat' Just Keeps on Rolling Along"". Rosetta. University of Massachusetts. Retrieved January 5, 2006.

- ^ Asch 2008, p. 108.

- ^ a b Philip 1993, p. 59.

- ^ Kreuger 1977, p. 54.

- ^ Ellison, Cori (December 13, 1998). "Porgy and the Racial Politics of Music". The New York Times.

- ^ Steyn, Mark (December 5, 1997). "Where Have You Gone, Oscar Hammerstein?". Slate. Retrieved January 5, 2006.

- ^ Eyre & Wright 2001, p. 165.

- ^ Norvell, Scott; & S., Jon (March 18, 2002). "The Show Can't Go On", [1]. Fox News. Retrieved January 2, 2006.

- ^ Lathan, Peter (October 24, 1999). "A More Subtle Form of Censorship" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine. The British Theatre Guide. Retrieved January 14, 2006.

- ^ a b Saviola, Gerard C. (April 1, 1997). "Show Boat – Review of 1994 production". American Studies at University of Virginia. Archived from the original on October 12, 1999. Retrieved January 5, 2006.

- ^ Richards, David (October 3, 1994). "Show Boat; Classic Musical With a Change in Focus". The New York Times. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- ^ Henry, William A. III (November 1, 1993). "Rough Sailing for a New Show Boat". Time.

- ^ Daniel, Douglass K. "They Just Keep Rolling Along: Images of Blacks in Film Versions of Show Boat". Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Minorities and Communication Division. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved December 31, 2005.

- ^ Briggs, Joe Bob (May 7, 1993). "Joe Bob Goes to the Drive In". The Joe Bob Report.

- ^ Laporte, Elaine (February 9, 1996). "Why do Jews sing the blues?". The Jewish News Weekly of Northern California.

- ^ Gomberg, Alan (February 16, 2004). "Making Americans: Jews and the Broadway Musical – Book Review". What's New on the Rialto?. Retrieved January 6, 2006.

- ^ Shapiro, Ann R. (2002). "Edna Ferber, Jewish American Feminist". Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies. 20 (2): 52–60. doi:10.1353/sho.2001.0159. S2CID 143198251.

- ^ Regan, Margaret (April 13, 2000). "Facing the Music – A Revival of Show Boat Confronts the Production's Historical Racism". Tucson Weekly. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

References

[edit]- Asch, Amy, ed. (2008). The complete lyrics of Oscar Hammerstein II. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780375413582.

- Barrios, Richard (1995). A Song in the Dark: The Birth of the Musical Film. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195088113.

- Block, Geoffrey (1997). Enchanted Evenings: The Broadway Musical from Show Boat to Sondheim. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510791-8.

- Block, Geoffrey Holden (2023). A Fine Romance: Adapting Broadway to Hollywood in the Studio System Era. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197501733.

- Bloom, Ken; Vlastnik, Frank (2004). Broadway Musicals: The 101 Greatest Shows of all Time. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. ISBN 1-57912-390-2.

- Dietz, Dan (2019). The Complete Book of 1920s Broadway Musicals. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781442245280.

- Dietz, Dan (2018). The Complete Book of 1930s Broadway Musicals. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781538102770.

- Dietz, Dan (2015). The Complete Book of 1940s Broadway Musicals. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781442245280.